In the spirit of promoting Filipino arts and culture, Pintô Art Museum continues to expand. But its former curator Riel Jaramillo Hilario—an artist and art historian—views it differently.

On Black Saturday last week, Social Media was abuzz about a post that revolved around the Pintô Art Museum. Riel Jaramillo Hilario wrote the article, a multi-paragraphed post he prefaced with the words “Caveat Emptor: Beware of the Door,” touching on the well-known exhibition space and its treatment of artists and their displayed works.

“I received a number of complaints about Pintô Art Resort este Museum daw from many artists saying they felt belittled by its management,” the post begins.

Hilario, a visual artist and art historian, was a former curator of Pintô. He’s been participating in museum activities since the early 2000s. In an interview with Lifestyle Asia, he paints a picture of the purported mismanagement of Pintô and its direction to growing the contemporary cultural institution.

Rise of issues at Pintô Art Museum

“I was among the artists community in the early 2000s who supported Dr. Joven Cuanang and his Silangan Foundation for Culture and The Arts to draw up plans and programs for what eventually became Pintô Art Museum,” shares Hilario. “Dr. Cuanang is a generous soul who is a rare art patron who opened his house to artists like us who needed studios way back then.”

From spearheading exhibitions like The Waiting Game (a show on jueteng) and Taimis Project (a multi-media interactive installation), establishing Pintô International (the international arm of the museum), to writing a book on Pintô Art Museum’s collection featured in the 2018 Art Fair Philippines and more, Hilario had plans to help the museum become a greater institution.

But upon returning from his travels in 2017, however, conflicts apparently arose. “This is also the time when I was told that the artist community—which was vital in the early years of the museum—is no longer involved in the policies of the institution,” he shares.

On top of his experiences of being discredited for his projects, the museum’s practices increasingly went against his beliefs and values. “The museum has new directions and visions now,” he claims.

He says that the increasing issues and his strong desire to fight for the rights of and alongside his fellow artists urged him to write the Facebook post.

Riel Hilario.

A possible work of mismanagement

“Many of the artworks in the collection are either suffering from the elements, dust, [or] insect infestation,” says Hilario.

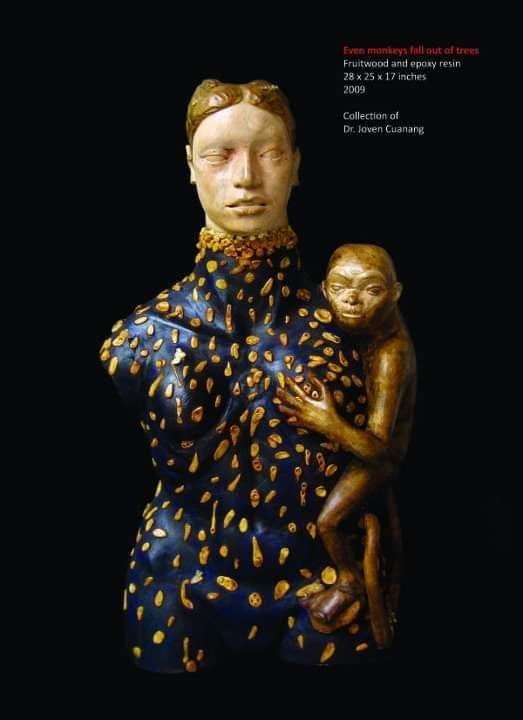

He shares an incident when the staff allegedly informed him that one of his works in the museum, The Lady of Revenge, apparently fell. This caused the head of the six-foot wood, metal, and fiberglass sculpture to break.

“When I brought this to the attention of the museum manager, she nonchalantly said that a cat did it… To make matters worse, when I offered to repair it, of course with the proper charges, she said if it was just possible to use glue,” the artist alleges.

Similarly, he claims many other guests including students of museum studies have already reported the poor condition of the artwork. This, and his strong desire to fight for the rights of his fellow artists, urged him further to go public with his side.

But, as with his broken sculpture, the management seemingly didn’t have concrete actions to officially address the concerns. “I received no response [from them] despite the post reaching 5,000 likes and almost 3,000 shares,” he says.

As of this writing, Lifestyle Asia reached out to Pintô Art Museum’s founder Dr. Cuanang about the social media post and complaints, but he declined the interview for now.

Riel Hilario.

Changing the standards

Beyond the conservation of the artworks, Hilario brought up the issue of compensation in his social media post.

“Lately we have been noticing that Pintô has been a bit inequitable with compensation,” he says, referring to fellow artists. He cites an incident of the museum commissioning him for a writing project, but they had given a “limited budget and time.” He attributes the conflict to the management’s lack of understanding of the process of art-historical writing.

Similar to the miscommunication with compensation, he is intent to renegotiate the system in commissioned works. Currently, Pintô “charges 50 percent commission for artworks sold,” as the artist said in his post. This is an industry-standard and in the country, “galleries unilaterally imposed this for close to ten years now,” the artist adds.

However, Hilario says that artists “deem this unfair” and so they are presently working to discuss a change in these terms.

Advocating rights

As more people visit Pintô, sometimes dubbed as “one of the most Instagrammed museums in Asia,” Hilario expresses disappointment over how it evolved into a tourist destination.

The artist asserts that the artworks are turning into mere displays, treated beyond the realms of the creative and cultural landscape. “The art market is lopsided toward the purely commercial and speculative aspect of sales and market segments,” he continues.

This is why his discussion with Istanbul-based photographer Wawi Navarroza about the creative industry’s role in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of a nation inspires Hilario to continue fighting for their rights. “Richard Buxani, a metal sculptor and I, organized the Art Response Project last year with the Iloilo Museum of Contemporary Art or ILOMOCA to address artist rights issues and I’ve been campaigning for a Magna Carta for Artists Rights since then,” he explains.

On top of these projects, he is also creating Daloy Likha in Quezon. The art and nature hub aims to establish a community with the locals and artists in places like Infanta, Pagsanjan, and San Mateo. “I wanted Pintô to realize [its] pivotal role in advocating artists’ rights as a museum built by the artist community,” he firmly says.

Space for growth

“I was told that the museum philosophy regarding art is that ‘everything is ephemeral,’” shares Hilario. When the museum was established in 2010, it has carried its name ‘pintô’ based on the principle of art connecting different views, identities, and communities. This reflects how the museum continues to present rotating exhibitions of its collections, featuring a roster of contemporary Filipino artists.

While he agrees with this art philosophy, he believes it is contradictory to how the museum treats itself as an institution.

At present, Pintô Art Museum is not accredited by The National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA). This is why in his former role as the curator, Hilario pushed for Pintô’s accreditation, together with the Philippine National Committee of ICOMOS, an international non-government organization dedicated to conserving monuments and sites across the world.

“I know the museum was already working with the National Museum with this but that program seemed to stall in favor of building expansion,” the sculptor shares. Last February, Pintô launched “The Pinto Arboretum of Philippine Plants,” a cultivated green space filled with endangered indigenous Philippine trees and plants.

The green center is the latest addition to the sprawling compound, on top of the existing main building, Gallery 7 (the new wing that opened in early 2020), Café Rizal by Peppermill (the in-house restaurant), Pintô Museum of Indigenous Art, and Pinto Academy of Arts and Sciences.

While there remains no official statement from the Antipolo-based exhibition space, Hilario hopes his advocacies, especially the Artists Association of the Philippines, may become a necessary sectoral representation to allow “artists and creative voices to be heard.”

Sculpture photos from Riel Hilario while museum photos are from the website of Pinto Art Museum.