One of the country’s top educational institutions continues the struggle on achieving its mission of shaping “men and women-for-others.”

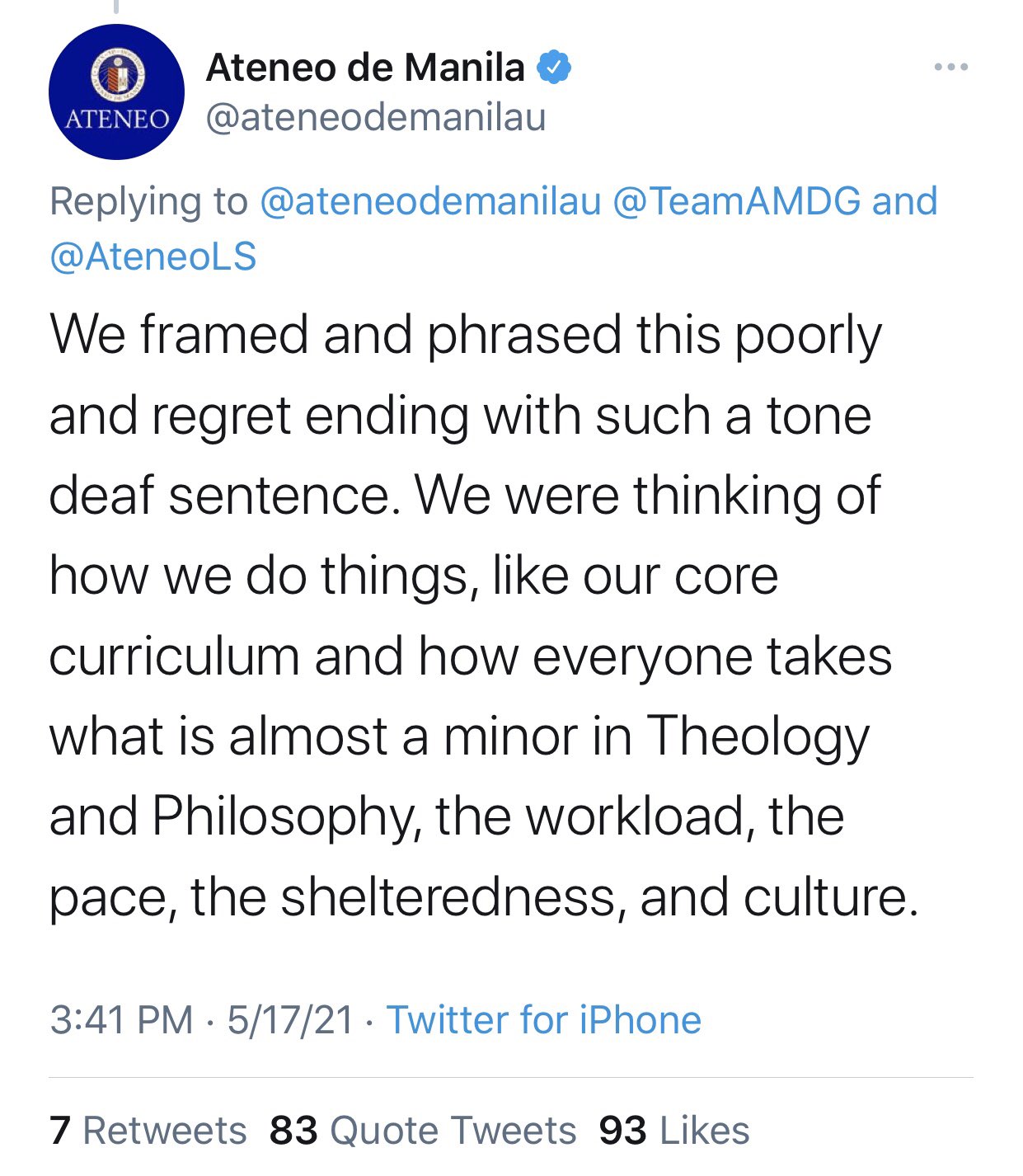

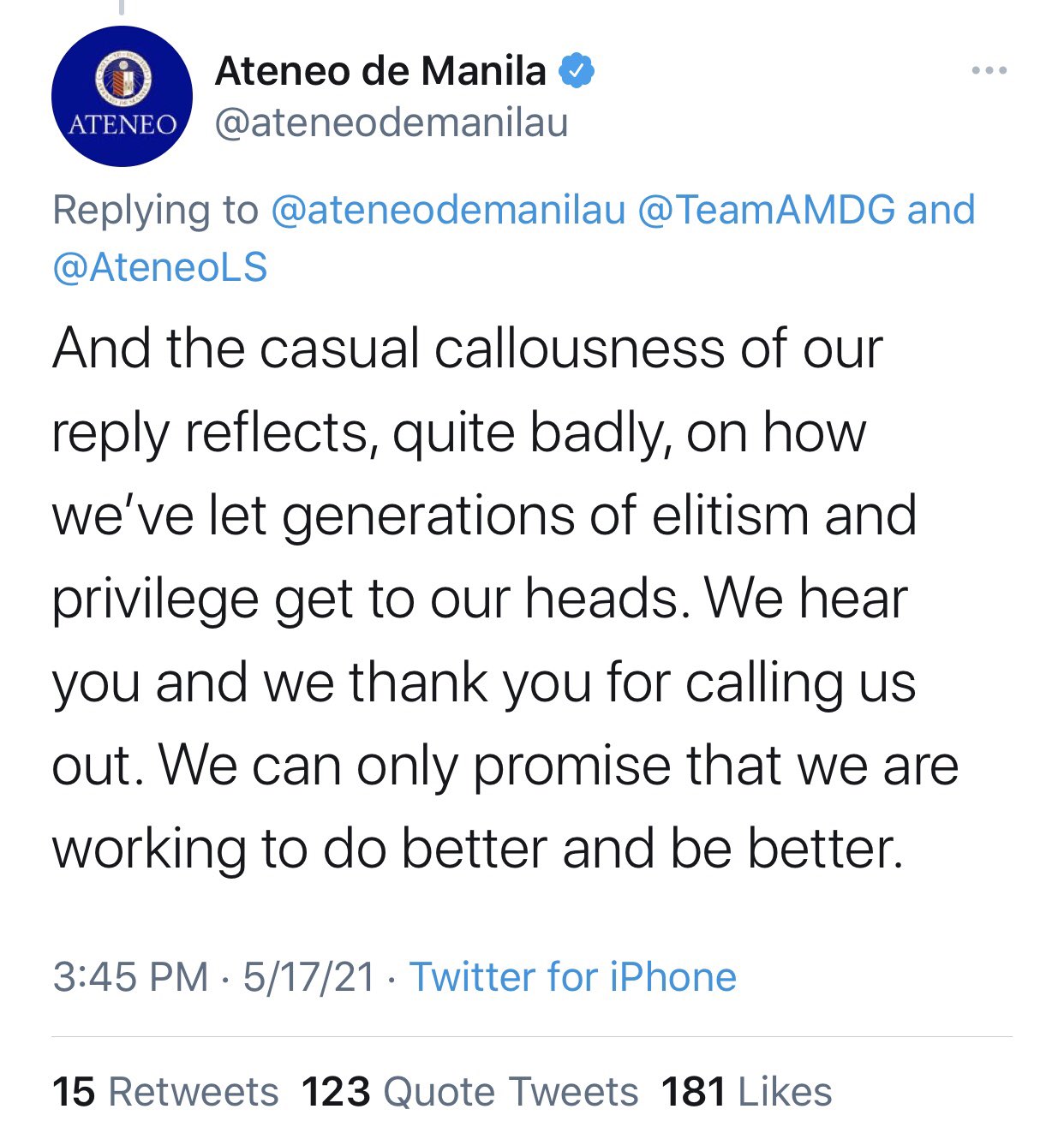

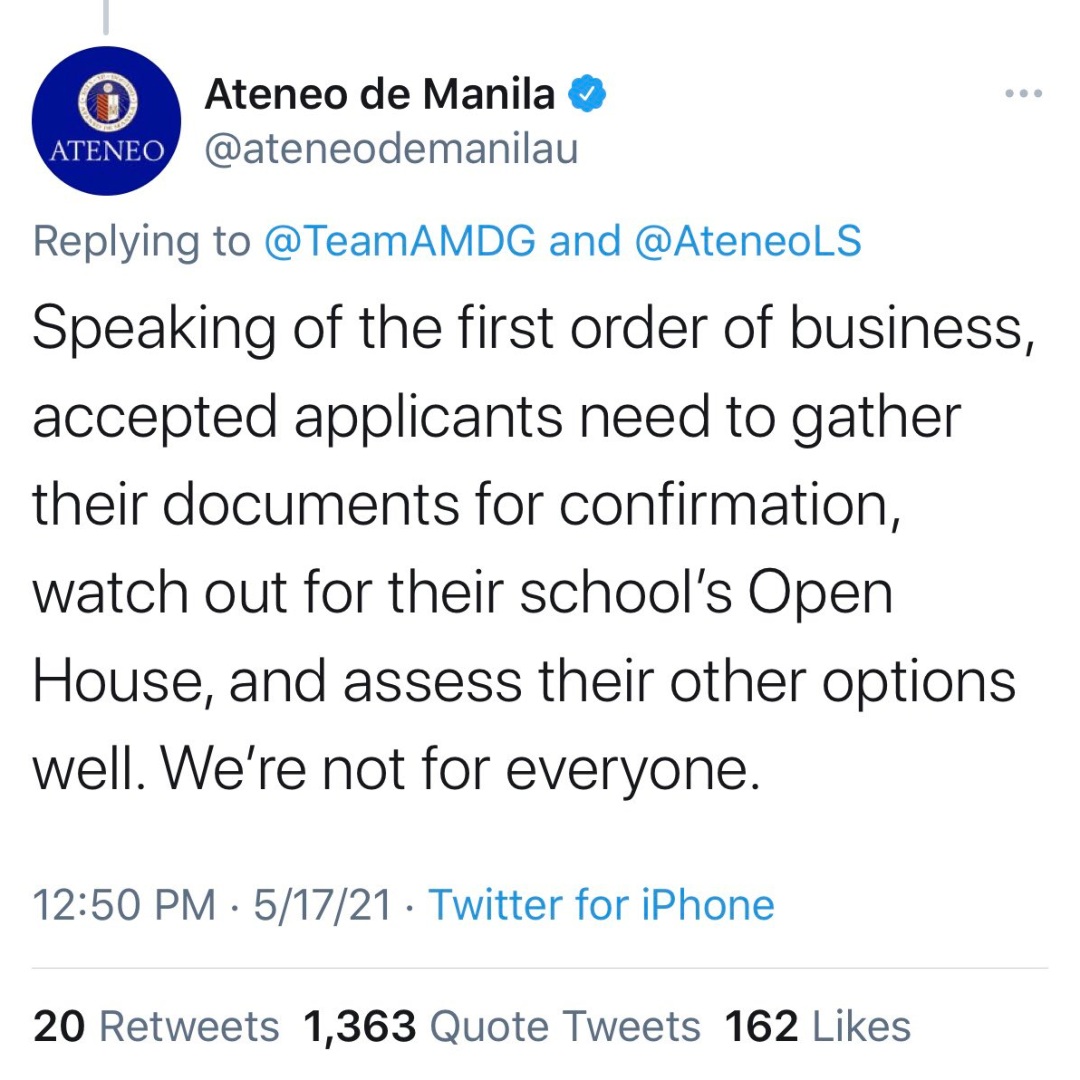

“We’re not for everyone,” says the official Twitter account of the Ateneo de Manila University last May 17 this year. The tweet was a reply to the Team AMDG’s post welcoming the freshmen of the school year 2021. The university issued a public apology and the viral tweet has been deleted. Yet social media remains abuzz with the striking statement, provoking discussions on the elitism and privilege Ateneo has long been associated with.

History repeats itself

The account may have followed the apology with a promise to “do better and be better” but it still received criticism for its elitist remark. However, this is not the first time the university has been reproached.

In 1968, an “explosive” manifesto was published by Ateneo’s official student newspaper, The GUIDON. Titled “Down From The Hill,” the manifesto was written by Ateneans Emmanuel Lacaba, Leonardo Montemayor, Jose Alcuaz, Gerardo Esguerra, and Alfredo Salanga, who all earned a period of suspension.

The controversial piece was deemed radical not only for speaking of the political landscape in the country before Martial Law but for its detailed discussion on the elitism of Ateneo.

The writers primarily called for Filipinization as it used to be American Jesuits who supervised the university. Naturally, the education was Westernized and unsuitable for the Philippine context.

Although more than 50 years have passed since then, it remains relevant as Ateneo proves it transformed into a brand hinged upon privilege. The university’s mission is to train men and women for others, but not much has changed when paralleled with the manifesto’s assertions.

Restructuring the institution

The manifesto criticizes the inability of the university to project the image of the Filipinos.

“We condemn as preposterous a myth the claim that the Ateneo is a training ground for true Filipino leaders. The true Filipino leader demanded by the revolutionary situation should be one who is oriented to serving the oppressed masses of his countrymen.”

The university did restructure its curriculum based on this call. Currently, the institution prides itself on its holistic approach to education. Integrated formation programs and services focus on the undergraduate students’ personal, social, spiritual, communal, physical, and leadership development.

With these came the National Service Training Program (NSTP), Junior Engagement Program (JEEP), and immersion programs that ultimately develop awareness of the students’ responsibility as “professionals-for-and-with-others.”

Another major change is when the Sanggunian ng mga Mag-aaral voice has been instrumental in leading political movements inside the campus.

For instance, when the Supreme Court sanctioned the burial of the former president and dictator Ferdinand Marcos at the Libingan ng Mga Bayani, students, professors, and staff expressed their dissent. After all, recognizing the dictator as a hero equates to forgetting the nation’s collective pain during the repressive regime.

Despite the recent adjustments, the actual impact of some of these programs remains questionable. The university even requires freshmen to undergo Introduction to Ateneo Culture (InTACT). It is a year-long subject offering students a glimpse into the so-called “Ateneo culture,” helping them develop skills to cope with the demands of college life.

Perhaps, this is related to what Ateneo cited in its apology, “We were thinking of how we do things, like our core curriculum and how everyone takes what is almost a minor in Theology and Philosophy, the workload, the pace, the shelteredness, and culture.”

The very notion of a distinct culture in Ateneo and the viral tweet’s explanation reinforces an elitist reputation and privilege that comes with studying and graduating from the university.

The true impact

The manifesto’s writers envisioned Ateneo to produce willing and capable individuals of going “down the hill.” This means stepping beyond the comforts of their fortunate background fraught with opportunities.

The ideal graduates are not “capable of being accepted in the best graduate schools abroad but instead graduates who are capable of solving Philippine problems based on Philippine standards and conditions…”

While indeed there have been changes to the administration and curriculum, are these programs enough to make Ateneo relevant to the country’s situation? Once the students step out of the campus, do the alumni truly serve the marginalized? Do they revisit the communities they engaged with, and use their current positions and opportunities to help?

The University administration has failed to respond to the national government’s dismissal of students’ right to protest—this signals that the Down from the Hill manifesto’s call for Filipinization remains relevant nearly 52 years since its publication. pic.twitter.com/aMzBZ9J7gT

— The GUIDON (@TheGUIDON) November 20, 2020

Beyond the students, the manifesto also encourages the administration to engage. “We recommend that the faculty involve themselves directly with the Philippine situation by taking positions on Philippine problems.”

However, even within the university itself lies a clear struggle and indecisiveness to take action on pressing issues such as employees demanding higher wages, sexual harassment cases, and dismissal of the students’ rights.

Looking back since the manifesto was published, it appears the Ateneo is far from achieving its mission. From the critical matters to careless statements claiming, “we are not for everyone” demonstrates the manifesto’s point: “We find the Ateneo today irrelevant to the Philippine situation because it can do no more than service the power elite.”

For now, the closing statement of the manifesto still proves to be relevant: “We, therefore, urge the whole university community to address itself to the problem and to face it squarely. Let us look deep into our hearts and ask ourselves if we are really willing to pay the price in terms of personal and communal sacrifices.”